"The old forms of communication are not unaffected by the development of new ones, nor do they survive [unscathed] alongside them." (Bertolt Brecht, on film).

Atom Egoyan showed his new film, Citadel, for the first time in the U.S. last weekend, at the University of Chicago. It is framed as a future gift to his son, who at the time of filming, was only 10, too young to absorb what his father was offering him: a portrait of his parents during their trip to Lebanon in 2004. Beirut was the home to his wife, the actress Arsinee Khanjian, before her family's escape from civil war and Egoyan records her return with brief glimpses of what life in Beirut was like before the Israeli air-strikes of this past summer. Egoyan seems to be innocently filming, naively catching family banter and the dense mix of contemporary cityscape, ancient ruins, and regions of war scars, all saturated with lush Mediterranean light.

But because he is more of a theorist of images than one who simply makes them, it does not take long to always be on the alert for what is not in the frame. The camera lens is repeatedly leading to something tight and close . . . always, then, to Egoyan himself. You cannot get away from him. If you want to see the room he shows you a book that he reading. When he pans through a gorgeous library in the early section of the film he comes to rest on his own reflection. Where he once shoots the room now he films his own image. That's all there was, he seems to be saying, and as much as the apparatus of the small, pocket-sized camera makes every object a target and every man, woman, or child a "director," the surfeit of images contained still pushes us back into the problems of seeing and choosing, and focus.

In this way he consistently, or rather compulsively, suggests more about the limitations of images than allowing one to ever settle into the content. Teasing out the provocative possibilities, by quietly drawing attention to what isn't shown, is what he does, whether it is in this home movie, or his feature films like Exotica, Ararat, or The Sweet Hereafter. In this way they are films that are in some sense absent from themselves, hollowed out so that watching them one is perpetually aware of watching a movie. (Even when he and his wife took questions from a large, rather stifled audience in the auditorium after the film's screening, it was impossible not to be aware, all the time: I am watching two filmmakers on a stage in a dulled auditorium. One was neither bored nor captivated. I am here, I am seeing, I am thinking . . .).

Like his character from Ararat, the Armenian-Canadian, Raffi, who travels to Turkey in a desperate attempt to make the landscape of the Armenian Genocide meaningful by filming it, Egoyan works in a kind of perpetual disappointment with what his camera cannot capture, the perversity, as he says at the film's end, that of all the stories circulating through the city streets, he has told his son only one, an internal family drama (about his compulsion to film, and Khanjian's to perform; though she nothing of a starlet--she is beautiful and smart and present and there is thus something strange about watching someone so comfortable in front of the camera, the quiet, steady narcissism of engaging, absorbing eyes).

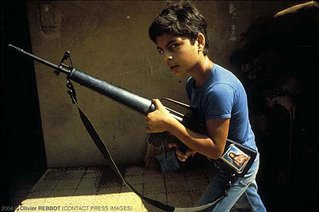

Egoyan calls his film an act of faith. Here he is telling his son about the civil war from 1975-1990, about the factions within the city, the almost rapid killing that went on, and about the infamous massacres of Palestinians in the refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila: homeless and displaced persons slaughtered out of revenge and perhaps, simply because it was possible. The details he recites get lost in the sunshine. There is almost no point in gesturing towards that history. It remains something remote, a documentary subject. He edits into this scene on the beach pictures of the war he taped off the television, as if they are what is there, buried in the sand. Image heaped on image, displacement and the struggle to focus. They are dark and muted with static, the war is an invisible thing now, or was until the devastation came again in 2006.

Egoyan calls his film an act of faith. Here he is telling his son about the civil war from 1975-1990, about the factions within the city, the almost rapid killing that went on, and about the infamous massacres of Palestinians in the refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila: homeless and displaced persons slaughtered out of revenge and perhaps, simply because it was possible. The details he recites get lost in the sunshine. There is almost no point in gesturing towards that history. It remains something remote, a documentary subject. He edits into this scene on the beach pictures of the war he taped off the television, as if they are what is there, buried in the sand. Image heaped on image, displacement and the struggle to focus. They are dark and muted with static, the war is an invisible thing now, or was until the devastation came again in 2006.

The autofocus latches onto its object mechanically. What are we compelled, by habit, to see? Or what is we choose to make disappear? How do our reflexes lead us or away from what should be closest, to some future focal plane. What you cannot see does not exist. This is a grave problem for Egoyan, who seems always undone by what he cannot see and what becomes the object of focus: out of habit, necessity, obligation, or obliviousness.