Inconsolable a woman

stands at the window,

a children’s swing

rusts in the wind

--W. G. Sebald, After Nature

At the close of W. G. Sebald’s book-length poem, After Nature, the speaker extends an unusual gesture. Apart from the predominantly solitary travelers who would later populate his work, here a father takes the hand of his daughter, promising to lead her on an “excursion,” one animated with the quiet “resolve / to make a new start.”

This is the Sebaldian sensibility: a route toward the future bound to go the way of the past, unwavering in the acknowledgement of struggle; the fitful exploration of “all kinds of lore.” And so we imagine father and daughter together noting the objects that emerge from the English countryside like archeological birthings, crossing the sites of ancient and modern history, all of it furrowed into the landscape they inhabit, however tentatively, together.

“A great enigma, my child,” he says, filled with the troubling wonder of her inheritance, and his own. This generational communion, at once demanding and assuredly gentle, a mode of love passing through the unavoidable pain, this effort of real recognition is, he says, theirs alone. It cannot be shared. First, because those who live daily on that history-drenched land drift by it all un-noticing—their imaginations immune to the vast reservoir of the past's presence. Certainly worse, they, father and child, will feel alone and cut off from the world as it is, trapped by the brutalizing present and the cold currents that shape life. These currents mirror the scene, the shoreline's "mummuring surge," the ocean’s relentless malevolence, a churning, thoughtless destruction. Sebald gives us the barest hints of this world's menace but we feel it all around us and know, intimately, through his exhausted tone, the destruction sponsored.

All around them, in the most personal and passing ways, the origins of that sponsored destruction: the pestilence of a certain pride, a devouring rapacity. It is the kind rationality activated through moralistic righteousness, or entitlement, or even, pitiably, as a defense mechanism for petty affronts; where there is more proper cause, more stringent images of horror, some thing unattainable becomes cause of the “inconsolable” wounding. So an armoring remoteness bred of obsessive impulses: agape at spectacles, manufacturing cheap and glittering joys, posturing with the worst clichés; banal, alienated, and vulnerable, unable to analyze complexities with feeling, or approach complex feelings through analysis, or engage anything with suppleness, and thereby feel as real the world’s incurable hardships. A destructive arrogance arises. The results are clumsy and cruel. Symptomatic of a desperate loneliness this way of being paradoxically finds solace in the dense, dying encampments of those imagined as like-minded. Apart from this, the father recalls the human failings and their mythic form:

As for the burning city,

in the Vienna Art-Historical Museum

there hangs a painting

by Altdorfer depecting Lot

with his Daughters. On the horizon

a terrible conflagration blazes

Devouring a large city.

. . .

When for the first time I saw

this picture the year before last,

I had the strange feeling

of having seen all of it

before, and a little later, crossing to Floridsdorf

on the Bridge of Peace,

I nearly went out of my mind.

Sebald's German family held this history within it like a cancer. Consequently, the short stories, poems, and novels that emerged from his emigration and returns to Germany bring catastrophe unbearably close, as intimate as a family photo album and his own father's sealed silence.

The father in After Nature remains burdened by that place he held as a child. He is filled with the need to know the texture of the world into which he came. His voice carries the past in multiple layers so dense that the mythic cities on the plain are overlaid with the burning cities of Germany’s defeat, the dark fortresses of torture and annihilation and the all the human-dreamt inhumanity akin to the secret motivations or insensitivities of his family.

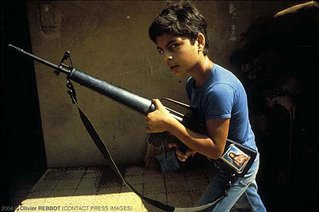

And so if there is the myopia of selfishness that this father and daughter are to fear, there is likewise, often entwined, that aggressive militancy in need of its victim, its target, the cause for violence. If Sebald's father could not teach him that, the lesson was learned well enough so that here, in the poem, the father, emigrant and exile, warns the daughter:

warriors even now

on this sandy strip keep their weapons

hidden in grassy bunkers . . .

one great

arsenal as far as your eye can see,

and nothing else but this sky,

the gorse scrub now and then,

an old people’s home,

a prison or an asylum,

an institution for juvenile delinquents. . . .

Inconsolable a woman

stands at the window,

a children’s swing

rusts in the wind, a lonely

spy sits in his Dormobile

in the dunes, his headphones

pulled over his ears.

The only antidote to the alienation and the knowledge of such a condition is the trust in the excursion, the hand in hand gestures that, with whatever solitude they require, bring one, and then another, to the point of truth, however late it comes, with whatever price of pain.

If Sebald was haunted by his own father's inexplicable silence, further haunted by his nation’s refusal to bend to responsibility and truth, in his poem he posits another generation of father and daughter.

They may be bound to the Lear-like wanderings, rummaging through the measure of their state of emigration, the destructive principal from which there is seemingly no escape. "Is this the promised end?" If not the end of sorrows, for they are endless, there is faith in a historical view that feeds the present with its purpose, that may go mad on the bridge of peace but still reaches with love for the daughter. And so, such a going-forth becomes their bond against the tide of all interference. Before them is the solipsism of the spy encased in his mobile home, the desolate woman alone and emptied before the childless swing, and there is then the "Whispering / madness on the heathland" -- the ceaseless production of destruction:

No, here we can write

no postcards, can’t even

get out of the car. Tell me, child,

is your heart as heavy as

mine is, year after year

a pebble bank raised

by the waves of the sea

all the way to the North,

every stone a dead soul

and this sky so grey?

How to be when the past is betrayal and the future promising its poison? "Is this love / nothing now / or all?" The question is reborn continually. No postcards can emerge from that space of communion, for there is only the living gesture of love enacted, tested always in the reception.

As for the greater proof of what remains, the remnants that form the future through which one must pass, it is easy, given Sebald, to imagine the dark and difficult family history yielding to the daughter’s open, questioning heart, should she open at all against the cold abuses of its environment. One imagines, if not postcards that mark a time and place of presence, then letters. One imagines the poem as a letter, a trace of experience the father has written and carefully saved. Yes, letters. They are marked for a future form of the past: as archives of photographs and true words held for a time of just reckoning: letters that testify, that move toward her, even as they wait, idle, dusty, gathering signs of fragility, both of inevitable entropy and hope in the tentative hold, hand in hand.