In his essay, "The Meaning of Working Through the Past," (1960) Theodor Adorno teases out the systems of avoidance at work in West Germany after the war. One aspect of denying the past its due consideration is a language of obfuscation that denies the past its immediacy. This language interferes with the critical self-reflection necessary to truly engage with the causes of the murderous disaster. For Adorno, the "mitigating expressions and euphemistic circumlocutions" turn the means of making the past present into a "hollow" discourse, or the death's head of thought. Forgetting becomes a thing done with words and not just a matter of their absence. More than for anything else, Adorno's fame or infamy can be traced back to his 1949 observation that culture turned rancid in the wake of Auschwitz. Then, he wrote:

In his essay, "The Meaning of Working Through the Past," (1960) Theodor Adorno teases out the systems of avoidance at work in West Germany after the war. One aspect of denying the past its due consideration is a language of obfuscation that denies the past its immediacy. This language interferes with the critical self-reflection necessary to truly engage with the causes of the murderous disaster. For Adorno, the "mitigating expressions and euphemistic circumlocutions" turn the means of making the past present into a "hollow" discourse, or the death's head of thought. Forgetting becomes a thing done with words and not just a matter of their absence. More than for anything else, Adorno's fame or infamy can be traced back to his 1949 observation that culture turned rancid in the wake of Auschwitz. Then, he wrote:

“Cultural criticism finds itself faced with the final stage of the dialectic of culture and barbarism. To write poetry after

Later he revised this suggestion, tempering it with the admission that torture demanded its scream, horror its poetic response:

“Perennial suffering has as much right to expression as a tortured man to scream; hence it may have been wrong to say that after

Perhaps no figure has been as closely associated with the phrase "poetry after Auschwitz" than the survivor, Paul Celan. His poetry's euphony may well still strike some as something transcendent if not barbaric. His insistence, however, is on the formulations of language that the dangerous talk of destruction and denial--which Adorno himself recognizes as a primary harbor of fascist tendencies--left in its wake. Accepting the Literature Prize of Bremen in 1958 Celan said of that which remained in the aftermath of "death-bringing speech":

"A poem, as a manifestation of language and thus essentially dialogue, can be a message in a bottle, sent out in the—not always greatly hopeful—belief that somewhere and sometime it could wash up on land, on heartland perhaps. Poems in this sense too are underway: theyare making toward something.

November 26, 2006

Doing Things with Words

November 21, 2006

Seeing the Sacred

The story comes in lovely simplicity and is embodied now in the ritual. Thanks given for a gifts of reprieve, humane encounter, the food of humanity, harvested from grace. The story says Tisquantum, a "native," emerges from the "wilderness," speaks to the Plymouth colonials in English, gives them the gift of harvesting corn, catching eels from the shore, becomes their interpreter and aids in the founding of the peaceful co-existence between the colony and the Wampanoag tribe.

Holocaust historian Omer Bartov recounts the following story of a seemingly grace-laden gesture. In the killing fields of Poland during the German Wehrmacht's push east in World War II anyone Jewish was deemed enemy, rounded up, and put in camps or shot in "actions." (During the war, such atrocities were in a sense hidden. They are still contested by those who wish to keep the reputation of the Wehrmacht safe from the crimes of the SS.) Jewish women in a labor camp outside Kracow are sent on a long march to the showers, bodies ravaged by the abuse, their feet torn apart by the wooden clogs they are forced to wear. Naked and bare the women realized German soldiers were adjacent to the showers, looking away, "perhaps out of embarrassment." Then, Bartov writes:

"one of the soldiers motioned them to come closer. [The women] froze in fear. But one of the young women ventured forward. As she reached the soldier, he took out a first-aid kit and dressed her bloody feet. And so they did with all the other women. This too happened; and although the same soldiers may have had plenty of Jewish blood on their hands, for one sacred moment in that war of genocide and destruction, they reached deep into their own humanity and helped to heal the wounded bodies and souls of a few doomed young women" (emphasis added).

The touch of a humane hand: the scholar writes about it as if we had witnessed something angelic emerging from the wilderness, the mass graves retreating into deep relief of consciousness, our imagination locked only on the scene of touch.

This is a habit of the imagination. Giorgio Agamben’s work on testimony, Remnants of Auschwitz, furnishes a powerful example of just this kind of temptation. At

This is a habit of the imagination. Giorgio Agamben’s work on testimony, Remnants of Auschwitz, furnishes a powerful example of just this kind of temptation. At

"This match might strike someone as a brief pause of humanity in the middle of an infinite horror. I, like the witnesses, instead view this match, this moment of normalcy, as the true horror of the camp. For we can perhaps think that the massacres are over—even if here and now they are repeated, not so far away from us. . . . But that match is never over. . . . It is the perfect and eternal cipher of the 'gray zone,' which knows no time and is every place. Hence the anguish and shame of the survivors . . . . But also hence our shame, the shame of those of us who did not know the camps and yet, without knowing how, are spectators of that match, which repeats itself . . . in the normalcy of everyday life. If we do not succeed in understanding that match, in stopping it, there will never be hope" (26).

For Agamben, “the match” in our time is all but invisible, and as spectators to barbarism we are deeply and continually implicated in what we will not see while focused on our humanity. In order to suggest what the Holocaust might mean, Agamben avoids such temptations, listening to what the survivors, through their witnessing, announce. Given what he calls the “non-coincidence between facts and truth, between verification and comprehension” how are we to understand the function of the survivor who bears the burden of witnessing? His reflections on testimony center around a silence, the unspeakable. This is as much a quality of what happened as it was something imposed upon those who suffered and died, or suffered and survived. This condition of silence is captured in the figure of the Muselmann, or what camp inmates called “The Muslim,” the camp inmate who had crossed an apparent threshold into a living death and who could not therefore grant testimony to their own destruction.

For Agamben, “the match” in our time is all but invisible, and as spectators to barbarism we are deeply and continually implicated in what we will not see while focused on our humanity. In order to suggest what the Holocaust might mean, Agamben avoids such temptations, listening to what the survivors, through their witnessing, announce. Given what he calls the “non-coincidence between facts and truth, between verification and comprehension” how are we to understand the function of the survivor who bears the burden of witnessing? His reflections on testimony center around a silence, the unspeakable. This is as much a quality of what happened as it was something imposed upon those who suffered and died, or suffered and survived. This condition of silence is captured in the figure of the Muselmann, or what camp inmates called “The Muslim,” the camp inmate who had crossed an apparent threshold into a living death and who could not therefore grant testimony to their own destruction.November 13, 2006

Image upon Image

"The old forms of communication are not unaffected by the development of new ones, nor do they survive [unscathed] alongside them." (Bertolt Brecht, on film).

Atom Egoyan showed his new film, Citadel, for the first time in the U.S. last weekend, at the University of Chicago. It is framed as a future gift to his son, who at the time of filming, was only 10, too young to absorb what his father was offering him: a portrait of his parents during their trip to Lebanon in 2004. Beirut was the home to his wife, the actress Arsinee Khanjian, before her family's escape from civil war and Egoyan records her return with brief glimpses of what life in Beirut was like before the Israeli air-strikes of this past summer. Egoyan seems to be innocently filming, naively catching family banter and the dense mix of contemporary cityscape, ancient ruins, and regions of war scars, all saturated with lush Mediterranean light.

But because he is more of a theorist of images than one who simply makes them, it does not take long to always be on the alert for what is not in the frame. The camera lens is repeatedly leading to something tight and close . . . always, then, to Egoyan himself. You cannot get away from him. If you want to see the room he shows you a book that he reading. When he pans through a gorgeous library in the early section of the film he comes to rest on his own reflection. Where he once shoots the room now he films his own image. That's all there was, he seems to be saying, and as much as the apparatus of the small, pocket-sized camera makes every object a target and every man, woman, or child a "director," the surfeit of images contained still pushes us back into the problems of seeing and choosing, and focus.

In this way he consistently, or rather compulsively, suggests more about the limitations of images than allowing one to ever settle into the content. Teasing out the provocative possibilities, by quietly drawing attention to what isn't shown, is what he does, whether it is in this home movie, or his feature films like Exotica, Ararat, or The Sweet Hereafter. In this way they are films that are in some sense absent from themselves, hollowed out so that watching them one is perpetually aware of watching a movie. (Even when he and his wife took questions from a large, rather stifled audience in the auditorium after the film's screening, it was impossible not to be aware, all the time: I am watching two filmmakers on a stage in a dulled auditorium. One was neither bored nor captivated. I am here, I am seeing, I am thinking . . .).

Like his character from Ararat, the Armenian-Canadian, Raffi, who travels to Turkey in a desperate attempt to make the landscape of the Armenian Genocide meaningful by filming it, Egoyan works in a kind of perpetual disappointment with what his camera cannot capture, the perversity, as he says at the film's end, that of all the stories circulating through the city streets, he has told his son only one, an internal family drama (about his compulsion to film, and Khanjian's to perform; though she nothing of a starlet--she is beautiful and smart and present and there is thus something strange about watching someone so comfortable in front of the camera, the quiet, steady narcissism of engaging, absorbing eyes).

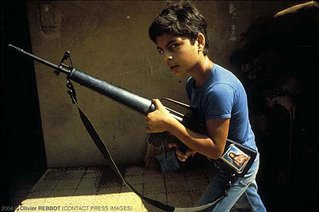

Egoyan calls his film an act of faith. Here he is telling his son about the civil war from 1975-1990, about the factions within the city, the almost rapid killing that went on, and about the infamous massacres of Palestinians in the refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila: homeless and displaced persons slaughtered out of revenge and perhaps, simply because it was possible. The details he recites get lost in the sunshine. There is almost no point in gesturing towards that history. It remains something remote, a documentary subject. He edits into this scene on the beach pictures of the war he taped off the television, as if they are what is there, buried in the sand. Image heaped on image, displacement and the struggle to focus. They are dark and muted with static, the war is an invisible thing now, or was until the devastation came again in 2006.

Egoyan calls his film an act of faith. Here he is telling his son about the civil war from 1975-1990, about the factions within the city, the almost rapid killing that went on, and about the infamous massacres of Palestinians in the refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila: homeless and displaced persons slaughtered out of revenge and perhaps, simply because it was possible. The details he recites get lost in the sunshine. There is almost no point in gesturing towards that history. It remains something remote, a documentary subject. He edits into this scene on the beach pictures of the war he taped off the television, as if they are what is there, buried in the sand. Image heaped on image, displacement and the struggle to focus. They are dark and muted with static, the war is an invisible thing now, or was until the devastation came again in 2006.

The autofocus latches onto its object mechanically. What are we compelled, by habit, to see? Or what is we choose to make disappear? How do our reflexes lead us or away from what should be closest, to some future focal plane. What you cannot see does not exist. This is a grave problem for Egoyan, who seems always undone by what he cannot see and what becomes the object of focus: out of habit, necessity, obligation, or obliviousness.

November 11, 2006

Cambodia Returns

Throughout Susan Sontag's Regarding the Pain of Others, the governing question is how we regard, or rather process, images of atrocity. If her work On Photography was devoted to the image itself, the politics of its reception comes to take precedence in this later work, for those images of atrocity are everywhere: perpetual pictures "speaking" on behalf of those in need of protection from the onslaught or terror, torture, endless war. The human rights theorist Michael Ignatieff claims that ideally those in need of protection can appeal for their rights, but what is the appeal held in the scream, or in the stammering translation of traumatic memory, especially when we only hear it through our seeing, sensing it from afar, and even then, through a regard that finds in the appeal, a beautiful picture?

Tuol Sleng is the infamous prison that was run by the Khmer Rouge of Cambodia. It was a center for the purging of Ankgar, the Organization of its supposed enemies: torture and carefully coerced, then scrupulously documented, confessions, and finally execution. Some 14,000 persons entered, seven survived. Everyone was photographed prior to their abuse and murder. As the anthropologist Lindsay French says of the images that remain, they are deeply disturbing and yet some are absurdly and arrestingly beautiful. They have appeared in galleries, they are for sale, they migrate in an economy of the image. Printed with care, they take on the accusatory and seductive power of an Avedon series; as if he had left the American West and just kept going to the other side of the world, some far side of experience.

How can these images be processed, imaginatively and psychologically? They play a prominent role in Rithay Panh's documentary S21: The Khmer Rouge Killing Machine, a film that brings one prominent survivor, Vann Nath, into "conversation" with several guards from the prison. He sits across from them, piles of photographs and documents on the table. The guards know the crimes they have committed and offer an array of defensive explanations. They remain "victims" and they themselves, they say, cannot "know" or process what happened there, even as they act out the rituals of the prison for Panh's camera. And sitting before the images, or even when forced into a forensic accounting of the murders they are distanced from the horrors; reading the pictures becomes a way of not acknowledging what the pictures show.

When thinking of human rights and their rhetorical necessities, it is hard to calculate the value of witnessing such things. One can stare at the images, one can consider the degradations and the systems of destruction--of human beings, of conscience, of moral injunctions. Even as they suggest some moments about what happened in that country, in that prison, in the aftermath, the images and their originating circumstance seem incredibly, and impossibly, far away. In order to stare, one needs time, and peace, and leaving the space of seeing them there will be a sunlit day, a city nightscape, an afternoon of work in a cafe, sustaining rhythms of safety and contemplation, which always brings with it a certain power and pleasure, no matter the substance of the thought. Of course, the two are always side-by-side, it's just a matter of accepting that fact.

As someone who saw the Tuol Sleng photographs rightly said, the proper absorption of the difficult, dis-heartening, and all the abject cruelties exacts its price. But that price is paid for the knowledge of what the human can do, what Aristotle might remind us to consider in our measure of worldly wisdom, the material that might come into play during the next rhetorical situation, when someone, or someone's image, makes its appeal. Along those lines, Sontag makes the claim that in today's world, no one has the right to be only, safely naive.

Learning to see what is shown and hear the translation of agonies from one dimension to another--often across borders, but more often through historical frames--makes demands. There are so many elements that disrupt our reception, some of them from without, some of them inside ourselves. The old definition of ideology used to be that it forced people to see the world upside down. "People know not what they do." The idea was that if they just learned the truth they would stop being selfish, cruel, heartless, unjust, etc. That definition has since been revised: "People know full well what they do, they just act as if they don't."

This has to do with investment and a willingness to understand--and to be critically engaged with--what one sees and encounters. Reading histories of Cambodia is to be struck by the degree to which those outside Cambodia argued about the truth of what was happening inside the country once it was controlled by the Khmer Rouge. It is true that there were no roaming bands of journalists operating inside the country, and that it took a long time for the realities there to take shape through survivor and refugee testimony. It might be equally true, however, that as Cambodia became a symbol (for a culture divided and at war over Vietnam) that how it was seen, understood, and misunderstood had a great deal to with the investments in seeing, or not seeing, the awfulness that existed there during that time.